Julia Tatiana Bailey: Visual Artists and the Politics of Surveillance in Post-Privacy America

Julia Tatiana Bailey is an art historian specialising in visual politics in the Cold War and art as propaganda, diplomacy and resistance. She recently completed a PhD focusing on official and unofficial Soviet-American cultural exchange and works as Assistant Curator of International Art at Tate Modern in London. Julia blogs on Cold War art at ESPIONART and can be found on Twitter @espionart and @tattyjewels.

In recent years, revelations about the mass surveillance programs of Western governments, and the extensive use and abuse of digital technologies on all sides of the so-called War on Terror, have brought the clash of privacy and national security to the forefront of public debate in the United States. The central role of the image within this debate makes it particularly relevant for visual artists and curators, who are keenly aware of issues arising from the creation, dissemination and reception of visual material. Criticism of government surveillance through digital channels develops concerns about the intrusive nature of the photographic medium that have been explored and debated by artists since the 19th century. In the 21st century, the distinction between documentation and voyeurism has been made all the more complex by the proliferation of images in an era of camera phones, CCTV, social media and reality TV. Yet as some condemn the perceived erosion of privacy, expectations of “artistic freedom” that have been enshrined in American culture since the Cold War are enabling artists and curators to provide a unique critical perspective on the contemporary politics of surveillance.

The conflict between claims of surveillance for protection and accusations of privacy violations has been a source of inspiration for a number of artists. Photographer Trevor Paglen has turned the camera back on those alleged to have infringed the privacy of others. His haunting photographs of spy satellites and classified aircraft, secluded listening stations and CIA prisons, penetrate the heavy blanket of secrecy shrouding covert government operations. However, Paglen has argued that rather than seeking to expose, his photographs instead aim to encourage viewers to question their submissiveness when faced with challenges to their personal liberties.

One artist only too aware of these challenges is Hasan Elahi. His experience of being mistakenly identified as a potential terrorist and repeatedly interrogated by the FBI in 2002 was a catalyst for a unique practice of self-surveillance. Since 2003, Elahi has made his location continuously available online through the Tracking Transience project, using the resulting data as source material for installations and performances. As well as critiquing the overreach of mass surveillance in the United States, Elahi’s decision to make his life publicly accessible has protected him from becoming a target of that surveillance.

Tracking technology has proved popular in the work of many artists in the United States, as well as other Western countries and beyond. Recordings and data capture from surveillance cameras have resulted in a number of site-specific installations and interactive public art projects by US-based artists including Camille Utterback, Christian Moeller, William Betts, and artist duo Electroland. Meanwhile, images and recordings harvested from CCTV cameras and everything from Twitter and Google Street View to eavesdropping devices and sexcams have been incorporated into works by Addie Wagenknecht, Paolo Cirio, Andrew Hammerand, Brian House and Kyle McDonald. Since 1996, the pro-privacy performance group Surveillance Camera Players (SCP) has staged silent spectacles in front of surveillance cameras in New York to protest their observation. By sharing these actions online, SCP has sought to communicate to audiences the vulnerability of all persons to surveillance. Other examples of how artists have appropriated surveillance technology to comment on its pervasiveness and validity have been featured in recent exhibitions such as Watching You, Watching Me at the New York offices of Open Society Foundations and Panopticon: Visibility, Data, and the Monitoring Gaze at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art.

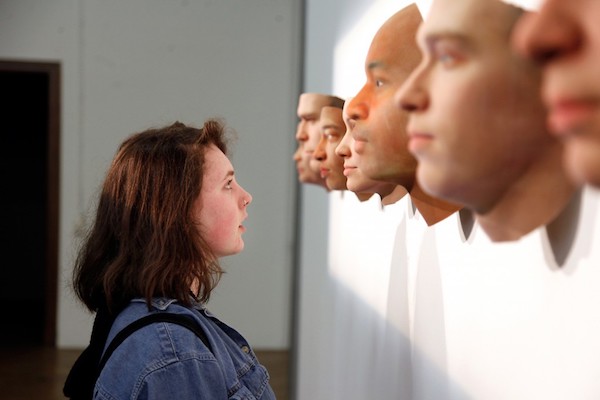

In an alternative approach to “surveillance art”, several artists have focused on the growing trend towards biometric surveillance. Between 2012 and 2014, Heather Dewey-Hagborg adopted techniques from biological surveillance to create a series of DNA portraits. The sculptures that comprise Stranger Visions were produced from genetic material found in public places to highlight the potential exploitation of the most basic elements of human identity. For his 2013 project CV Dazzle, Adam Harvey explored how modifications to hair styling and makeup could elude facial-recognition software by making people undetectable to computer vision algorithms. Harvey expanded on the theme in Stealth Wear, a fashion line that included an anti-drone burqa and hoodie. The typeface ZXX, created in 2012 by the South Korean graphic designer Sang Mun while he was an undergraduate at the Rhode Island School of Design, was likewise intended to be indecipherable by text-scanning software. Such artistic interventions reveal the extent to which identities and personal information are compromised by new technologies, and question the unwillingness of the state to protect the rights of individuals.

American Jill Magid has covered this territory in several works, while collaborating with the “protective” institutions that have initiated surveillance programs. In 2002, she persuaded the Amsterdam Police Department in the Netherlands to let her decorate CCTV cameras at its headquarters for the performance project System Azure Security Ornamentation. Two years later, Magid created the video work Evidence Locker from CCTV footage of the artist recorded by surveillance cameras in Liverpool, England, with the assistance of the local police force. However, when AIVD, the Dutch secret service, commissioned Hagid in 2005 to create an artwork for its headquarters, in the hope of improving its public persona, she used her unique access to gather material for a series of independent exhibitions which were subsequently censored by the agency.

Indeed, as artists have joined the intelligence community and privacy campaigners in pushing the boundaries of legality, the defense of “artistic freedom” has enabled them to venture into both physical and critical areas restricted to non-artists. In 2006, the privileging of artistic expression above personal privacy was established by the New York Supreme Court in the case of Nussenzweig v. diCorcia. Ermo Nussenzweig, an Orthodox Jew, objected on religious grounds to his inclusion in Heads, a series of photographs of unsuspecting passers-by which had been taken by American photographer Philip-Lorca diCorcia on the streets of New York. The court consequently ruled that diCorcia had the right to record Nussenzweig’s image as an anonymous subject of his street photography, as well as to display, publish, and sell the resultant photographs without Nussenzweig’s consent. Although using genetic material also found on the street, Heather Dewey-Hagborg was cautious to research which states prohibited the usage of DNA in this manner, drawing even more attention to the potential for abuse. By using telescopic lenses to overcome the anti-espionage defences of classified sites, Trevor Paglen has co-opted photographic technology more often associated with paparazzi into his artistic practice. Meanwhile, photographers including Tomas van Houtryve have attached cameras to drones to capture images that provide a compelling vision of a future where government surveillance threatens to encroach further on civil liberties.

This post by Julia Tatiana Bailey is a companion piece to her appearance on episode 34 of the Covert Contact podcast. – John