Art as Espionage in Cold War America

Julia Tatiana Bailey is an art historian researching art as propaganda and diplomacy in Cold War America. She is currently completing her PhD as a Predoctoral Fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. She blogs twice-weekly on Cold War art at ESPIONART. You can follow Dr. Bailey on Twitter @espionart and @tattyjewels.

When in 1979 Sir Anthony Blunt, Professor of History of Art at the Courtauld Institute in London and Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures, was publicly exposed as a member of the ‘Cambridge Five’ Soviet spy ring, the worlds of art and espionage sensationally collided. Although the artist as a spy is a largely fictional phenomenon – save for a fantastical revelation in 2002 that Israeli spies had posed as art students in an attempt to gain access to US federal departments – the Cold War brought art and espionage closer than ever before.

From scenes of military victories on the tomb walls of Ancient Egypt, to the ghostly self-portraits of Felix Nussbaum produced during his years in hiding from the Nazis, the narrative of the artist at war, as witness or propagandist, has a long and distinguished history. With the advent of the Cold War, the relationship between art and war shifted. This new kind of confrontation, where armed conflict was replaced by psychological warfare, pushed culture to the front line. On both sides, art was increasingly cultivated as a weapon to be waged against the enemy, with artists recast as messengers of ideological dogma.

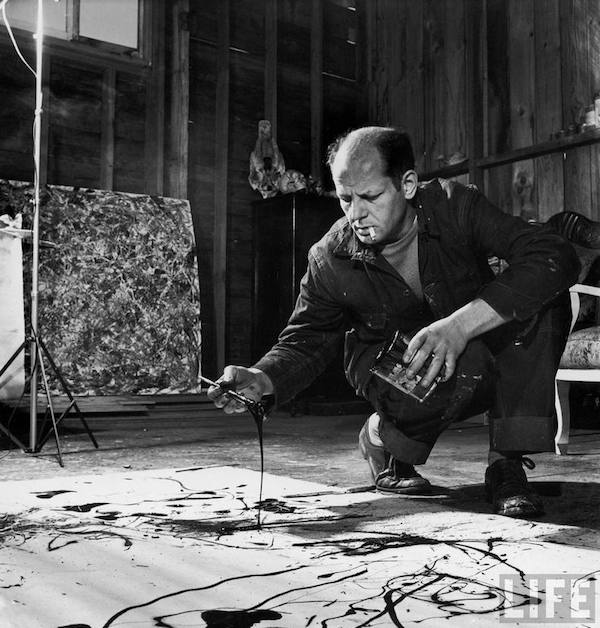

In 1951 the CIA declared in a classified report that ‘culture, like religion, generally permeates the souls of those imbued with it to such an extent that it is one of the last elements of independence purged out of the individual man under a totalitarian regime’ – and then proceeded to suggest how American art could be used to disseminate the nation’s ideals around the world. During the ‘50s, the visual arts reflected the polarised position of the two superpowers in diametrically-opposed styles of art: in the Soviet corner, Socialist Realism, a centralised doctrine that unequivocally reformulated all art as propaganda intended to inspire the populace to build a communist utopia; and in the American corner, Abstract Expressionism, seemingly untouchable by outside influence, so indecipherable as to be ineffective as propaganda and therefore credible as the ‘free’ art of a nation that held the rights of the individual above all else. With his smouldering stare and anti-establishment demeanour reminiscent of James Dean, Jackson Pollock was the poster boy for this new American art. Yet success forced Pollock and his fellow abstractionists into the covert employ of intelligence agencies with hidden agendas.

As McCarthyism raged in the United States, fears were raised of a communist conspiracy in the art world. Michigan congressman, George Dondero, led attacks against ‘subversive’ modern art and accused artists of being ‘soldiers of the revolution in smocks’. This condemnation prevented the United States from establishing an effective programme of international artistic display for most of the 1950s. Instead, organisations such as the Paris-based Congress for Cultural Freedom acted on America’s behalf. As part of their efforts to prevent the spread of communist ideology amongst the Western intellectual community, the Congress planned events such as the Masterpieces of the 20th Century exhibition in 1952 at the Musée National D’Art Moderne, intended ‘to illustrate the vigour with which art is flourishing in a free world’. When in 1967 the CIA was revealed as a covert funder of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, the line between art and espionage was one again blurred. Even when a treaty was finally signed in 1958 to enable official Soviet-American cultural exchange, sections of the media expressed their concern that this would open the door for the KGB ‘to send their espionage agents into this country posing as artists’. These fears had some validity, as staff on both sides of the exchange used their time in the rival country to gather intelligence on cultural and technological developments. Meanwhile, these visits also enabled a number of artists to defect across the Iron Curtain.

During World War II a group of eminent American painters were called upon to travel to the theatres of war to provide an interpretation of the ‘essence of war’ in order to encourage ‘the spiritual and psychological participation of the whole people’. The Art Advisory Committee of the US War Department declared: ‘the only psychic communication we have is through the arts’. Yet having signed government contracts and made travel preparations, three of those artists were unceremoniously removed from the project. Anton Refregier, William Gropper and Philip Evergood were found to be of unsatisfactory character according to the Hatch Act, due to their previous communist affiliations.

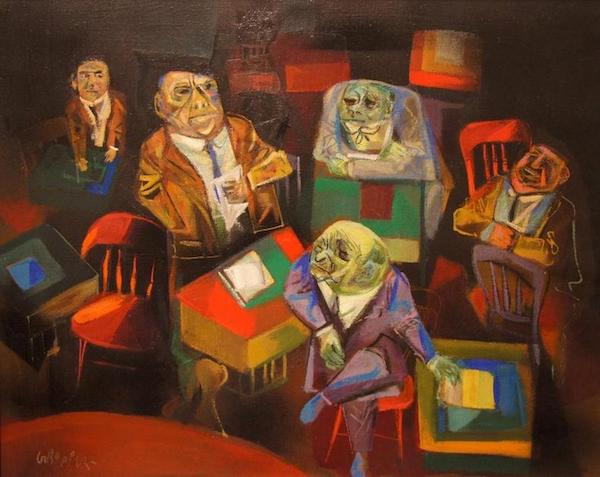

After their dismissal from the project in 1943, Refregier, Gropper and Evergood gravitated towards the National Council of American-Soviet Friendship in New York. Founded that year on the wave of the Soviet-American wartime alliance, the Council suffered a rapid drop in fortunes in the post-war era and was indicted for ‘subversive activities’ in 1947. Yet the group remained active and increasingly popular among social realist painters rejected by the powerful New York art museums in the 1950s. In 1957 Rockwell Kent, a prominent painter and illustrator and the Council’s new chairman, became the first post-war American artist to hold a solo exhibition in the Soviet Union. His example led to a growing desire for disenfranchised realist artists to exhibit their work in the country. Artists associated with the National Council of American-Soviet Friendship became fanatical opponents of abstraction and mouthpieces for the post-Stalinist Soviet policy of ‘peaceful coexistence’. Encouraged by material and financial support from the cultural authorities in Moscow, these artists willingly took on the role of agents for the USSR to breed animosity within the United States.

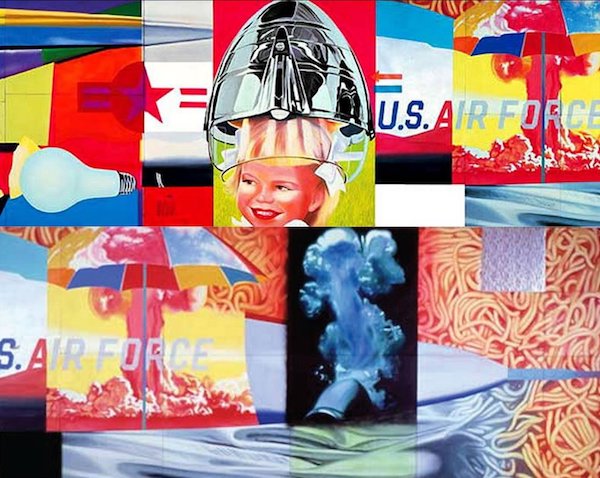

The overlap of art and espionage in the 1950s abated in the next decade. As skepticism built on either side of the Iron Curtain, state control of the arts faltered. In the United States, growing discontent with the Vietnam War and the rise of New Left activism inspired artists to express themselves in new ways which challenged political appropriation. Pop Art emerged as the leading artistic movement for the post-Kennedy generation. Andy Warhol produced multi-coloured prints of Chairman Mao and atomic bombs, while James Rosenquist depicted the F-111 fighter-bomber ‘flying through the flak of consumer society to question the collusion between the Vietnam death machine, consumerism, the media, and advertising’. In the Soviet Union, Khrushchev’s Thaw emboldened artists to push the boundaries of Socialist Realism, and Pop Art was mirrored in the anti-totalitarian satire of Sots Art. Despite the efforts of the authorities to crush the spirits – and the paintings – of this new generation of artists, the Nonconformist Art movement that developed in the 1960s would outlast the Soviet regime. Meanwhile, in Germany, Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke defected from East to West and established Capitalist Realism to mock the effect of Cold War politics on the visual arts. American art was finally infiltrating the Soviet Bloc – but not in the way the government had envisaged.