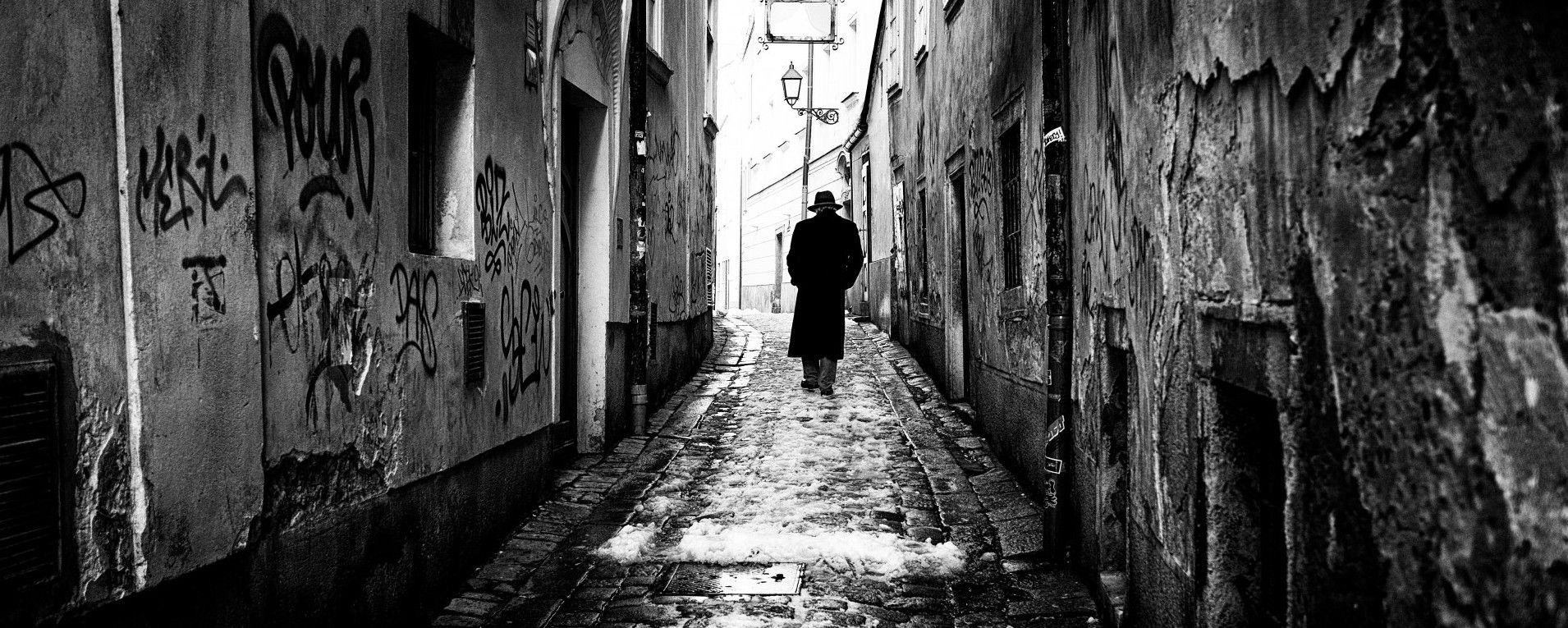

A Mossad Officer's Life in the Cold

Michael Ross was born in Canada and served as a soldier in a combat unit of the Israel Defence Forces prior to being recruited as a “combatant,” (a term designating a deep-cover operative tasked with working in hostile milieus) in Israel’s legendary secret intelligence service, the Mossad. In his 13 year career with the Mossad, Ross was also a case officer in Africa and South East Asia for three years, and was the Mossad’s counterterrorism liaison officer to the CIA and FBI for two-and-a-half years. Ross is a published writer and commentator on Near Eastern affairs, intelligence and terrorism. He is the author of The Volunteer: The Incredible True Story of an Israeli Spy on the Trail of International Terrorists.

John Little: John le Carre’s The Spy Who Came in from the Cold is a damning and deeply cynical take on the intelligence profession and government’s use of intelligence and intelligence operatives. It is an uncomfortable and exaggerated (but not entirely untrue) look at the difficult human dimension of this business that will always be relevant even as technological sources of intelligence continue to advance. In a world where relationships are often built on an inherent dishonesty, empathy for the source is secondary to achieving one’s goal (or non-existent), and success may also mean that lives are damaged or lost in the process how does an intelligence officer succeed and walk away relatively undamaged? Is that even possible?

Michael Ross: I think the great achievement of “The Spy Who Came infrom the Cold” is that it lifted the Bondian veil and revealed that spies aren’t all suave Aston-Martin driving sex addicts who gamble at high end casinos but what Le Carre’s anti-hero Alec Leamas describes as “a bunch of seedy squalid bastards like me.” While I think he is being a bit harsh in his assessment, I believe the underlying point he is making in this part of the book (and brilliant subsequent film with Richard Burton) is that people searching for some deeper, altruistic motive behind the actions of their intelligence services will be readily disabused of these notions when confronted with the reality of the profession. Le Carre posited that intelligence services are the sub-conscious of the nation they serve and when examined as such, you see that he has also revealed another hard truth about this milieu. I would only add to Le Carre’s observation by saying that intelligence services are also the disassociative aspect of a nation’s sub-conscious. Policy makers have a tendency to only ask questions about methods when things go awry.

A spy’s job is to meet the expectations set by his nation’s national security agenda (and in specific instances I include economic security under this umbrella) and part of this includes targeting people for sources of human intelligence who will assist you in meeting these expectations. From the dock-worker in Tartous to the network administrator for a European telecom provider, they all have to be spotted, assessed, developed, recruited, and handled by a spy in person. This involves forming a bond and workable relationship, but for obvious reasons, these relationships can only go so far. There can also be a great deal of warmth and empathy in these relationships that is often misinterpreted by the source (I heard of more than once case where a female source fell in love with her case officer), but it can never be reciprocated to the degree that it interferes with the primary objective of the relationship. A HUMINT case officer who lacks empathy and is unable to make some kind of bond with his source will never achieve the full potential of the relationship.

Things do go wrong from time to time and sources get caught and in our area of operation, this often means torture and death. I never saw a case officer remain unscathed by such an experience and I think one of the great fears of practioners is to lose a source. Some case officers are less moved by relationships with thier sources than others but in the end, it’s a question of balance; be the person that your source wants to spill his secrets to but don’t take it so far in the direction of cameraderie that your source is also your best friend. People know when sincerity isn’t genuine. Recruiting human sources of intelligence is as much an emotional and psychological construct as it is an intellligence gathering one.

John Little: The psychological dynamics of these relationships really run the whole spectrum so it’s difficult to generalize. However, agents seem to be burdened with most of the psychological stress. Once that line has been crossed and they’ve betrayed their country the case officer is both a lifeline and in some ways a potential (if not outright) threat. It seems like a really unstable dynamic. How were you prepared for this? Can role play and classroom time really prepare a potential case officer for the challenge or does it have to be mastered in the field?

Michael Ross: Let there be no mistake; it’s the source that bears almost all the risk. How often do you hear in the news that a Mossad, CIA, or MI6 case officer has been captured and/or executed? By the same token, being a case officer has its stresses and dangers (one of my Mossad colleagues was shot by a turned source during a meeting in Brussels and we all know what happened at the CIA base near Khost), but by comparison, it’s negligible compared to what the source must endure waiting for the local security goons to get wise. The worst thing a case officer can do is be the cause of his source’s capture. It’s why we do surveillance detection routes, have good cover, and make damn sure we’re not being the reason the source was discovered. The recent episode with Ryan Fogle in Moscow is a good example of what happens when you don’t take the HUMINT recruitment process seriously. You can laugh at Fogle and his wig but you have to wonder who trained him and even more importantly, thought he was a case officer worthy of deployment in Russia.

There is no replacement for experience but training is a very big part of success in the field. There is a lot of time devoted to role-playing during training. I can’t speak for other services but our role-playing consists primarily of real-life scenarios based on what happens when things go sideways. You have sources who balk, demand more money, threaten to go to their own authorities etc. I recall one Mossad case officer sitting calmly with his Arab source in a hotel in Zurich and the source engaging in histrionics and complaining bitterly about his lot in life. The Mossad case officer just smiled and reassuringly told the source in Arabic, “I kiss the words that come out of your mouth”. Sometimes all a source wants is reassurance and a chance to vent. A good HUMINT service always remembers that it’s dealing with human beings with all their failings and idiosyncrasies. A good case officer is able to evaluate very quickly what type of person he’s dealing with and conduct himself accordingly.

John Little: So maintaining a productive relationship with the source requires a lot of work. Does all the effort that goes into maintaining security and managing the agent’s psychological state help the case officer maintain the necessary emotional distance? It’s never really a “normal” relationship and it would seem that those extra layers of activity would constantly reinforce that.

Michael Ross: That’s an excellent way of framing the relationship. As a case officer, there is so much to be done in the professional domain that the logistics and requirements of the job prevent the relationship with your source from becoming a true “friendship”. It’s important to also remember that a case officer has other sources on the go at varying degrees of development at once and therefore is too busy managing each relationship like a plate spinner to somehow turn work into the kind of relaxing and fun construct that real friendship entails. The essence of real friendship is effortless, the essence of being a good case officer is making it look effortless when it’s not.

Having said that, there’s moments to debrief and there’s times when you can hit the bars and relax with your source. Some case officers are fun people and some are very businesslike. It’s a question of personal style and if it works, then nobody will question it. I’m an introvert at heart but the work forced me to overcome that part of myself and become someone else for the purpose of getting the job done. I actually enjoyed that transformation and still do on the rare occasions that I still have to step out on myself.

John Little: How does this dynamic change when a case officer’s leadership gets involved? It’s not too difficult to imagine a scenario where all three players have different expectations from the relationship. Do these kinds of breakdowns occur? Are there common strategies for managing this problem?

Michael Ross: The Mossad, because of its size and small cadre of case officers at its disposal, has to be really selective about the sources that it recruits. This means that the case officer’s leadership is involved in much of the process in a collaborative way. Having said that, I remember taking two senior managers from HQ to a country in Africa who had never visited before to meet some sources and one of the managers – who served in France – made a comment about the conduct of my source that I took rather personally. In defence of my source I made an angry comment about Africa not being exactly the same as Europe. I knew the terrain and the local attitudes and my manager was looking at it from the perspective of his experiences in Europe. I received a stern rebuke and the moment was instructive. I endeavored thereafter to educate my managers about the way business is done in the places I chose to serve and also remember that yes, a source needs his case officer to be his advocate with his own people from time to time.

Even in the most collaborative environment, the friction between field and HQ will always exist.

John Little: It sounds rare but when the collaboration does break down, and the case officer and leadership find themselves at odds, is there a specific approach to working that out or do they eventually end the conversation, pull rank, and force the case officer to carry out their instructions? And while we are on the topic is it fair to say that headquarters has to manage it’s case officers to some degree the same way case officers manage their agents?

Michael Ross: I don’t think I ever saw a complete break down between case officer and HQ but there are differences of opinion on how to approach a recruitment operation. These details are always hashed out in advance. Case officers are expected to work with little guidance and a fair amount of autonomy but the reporting structure makes sure that there is no real disconnect.

As far as case officer management goes, that’s a really interesting question because case officers tend to be people with subtle (and at times not so subtle) powers of persuasion and manipulation. Issues arise when case officers think it’s okay to use this finely honed skill in their personal lives and with colleagues at work. It’s considered very bad form in the Mossad for a case officer to try and use his skills on colleagues or as a means to advance his or her career. It’s extremely rare, but it does happen. Case officers (and combatants) are a special demographic that requires careful, but not overly stringent management. One of the advantages that the Mossad has is that it’s senior ranks are not professional bureaucrats but people who have earned their position through successful careers in the field – and these are not people to be trifled with. In fact, it’s not usual to have a new division head appointed that has barely spent anytime at all inside Mossad HQ.

John Little: Despite the Mossad’s laser focus on its mission, the excellent training and a generally effective chain of command I still get the sense that you can personally relate to the source of Alec Leamas’ cynicism. Can you, in very general terms, touch on the decisions or outcomes during your career that didn’t set will with you and perhaps still don’t?

Michael Ross: As someone whose career was almost entirely based in the field I can very much identify with Alec Leamas and his cynicism. There’s a great (and in my view under-noticed) part in “The Spy Who Came in From the Cold” where Le Carre talks about the essence of being a spy and living a life under cover: “In itself, the practice of deception is not particularly exacting; it is a matter of experience, of professional expertise, it is a facility most of us can acquire. But while a confidence trickster, a play-actor or a gambler can return from his performance to the ranks of his admirers, the secret agent enjoys no such relief. For him, deception is first a matter of self-defense. He must protect himself not only from without but from within, and against the most natural of impulses: though he earn a fortune, his role may forbid him the purchase of a razor; though he be erudite, it can befall him to mumble nothing but banalities; though he be an affectionate husband and father, he must under all circumstances withhold himself from those in whom he should naturally confide.”

For all the cool professionalism of my service as I describe it, there are the petty banalities that one cannot escape; the source you detest and yet must cajole and entertain, the bigot, the venal, the malodorous, and the foul. The constant and monotonous surveillance detection routes (try doing one in Delhi in 42 C. heat, it’s very unglamorous). Then there is your own desk officer who forgets to maintain your commercial cover address and brings your credibility into question within your operational environment, the constant loneliness, and the occasional failure. This is compounded by those instances where you are putting a source and his family at risk yet he knows it and agrees because you can help his family or keep him afloat financially knowing his dependency on you is like a drug. He’s your worst enemy and now your best friend. After someone looks at you in the way a drowning man looks at a life preserver, believe me that it changes you and makes you second guess yourself and who you really are. At the center is a sense of duty. This is the only place where soldiers and spies walk a common road; you are expected to do the worst things because it’s a contract you signed and fulfill because if you don’t, then who will?